Sacred Shadows

Britain’s new wave of spiritual cinema

If I ask you to think of British cinema, chances are you’ll bring to mind kitchen sink realism.

Bleak explorations of ordinary lives have become the defining image of Britain on film for decades now. Kitchen sink dramas first flourished in the 1960s and have persisted as the dominant genre right through to the last decade with films like Tyrannosaur. With only a few exceptions, this is a genre which has kept British cinema rooted in corporeality.

I’ve always thought this focus reflects the British knack for grounding ourselves in the grit of everyday life, eschewing the mystical in favour of the tangible. Whether that’s the product of a lack of imagination, or an aversion to the risks of faith, I don’t know. But the groove of gritty dramas has been well worn either way.

But maybe there’s change afoot. British cinema is becoming unmoored from its social realist anchor, with a new wave of directors choosing to explore stories which transcend the physical, ushering their characters from council estates and terraced streets to realms of mysticism and metaphysics.

These films do bear the weight of their predecessors’ social issue focus, but come at it with an emphasis on the eerie, disorienting and at times horrifying. Why the change? Did they all get together one day in a meeting room at the BFI Southbank and decide that kitchen sink realism was old hat?

A search for meaning in a world without any

I think it’s probably more likely a reflection of a modern search for meaning in a world where secular institutions and social intellectuals have little to offer in the way of guidance. Where then do we turn? Perhaps, as Mark Jenkin’s work suggests, we look to the mysticism of the land that used to sustain us. In Jenkin’s Enys Men (2022), a desolate Cornish island becomes the site of a disquieting exploration of duty, solitude and the uncanny. “I’m not on my own,” declares the unnamed protagonist - an unsettling revelation amidst the otherwise deserted, wind-swept island, and an apt declaration for this new age of mysticism in British cinema.

Jenkin uses grainy 16mm film, uncommon aspect rations, stark colour contrasts and heightened, offbeat soundscapes to evoke an elemental atmosphere out-of-kilter with regular time. We, and his protagonist, are drawn into a liminal space, stuck between past and present, life and death.

It’s not an entirely new thing for British filmmakers to drive us out to the intersection of the real and the otherworldly before.The ghost stories of Powell and Pressburger’s A Matter of Life and Death (1946) and Jack Clayton’s The Innocents (1961) brought a surreal edge to the otherwise straightforward fare of mid-century cinema.

Then directors like Ken Loach and Mike Leigh brought kitchen sink drama to its zenith, giving mysticism the old heave-ho in favour of a sharper focus on class, labour, and the oppressive struggles of working-class Britain. Faith and spirituality were largely absent from their narratives - as they began to be from people’s daily lives in general, because they offered no succour from the drudgery of the everyday. Instead, they were replaced by secular concerns grounded firmly in material reality - how can I survive today?

This lineage is what makes Daniel Kokotajlo’s work so striking. A former Jehovah’s Witness, Kokotajlo’s debut feature Apostasy (2017) follows a devout family grappling with the shattering consequences of their faith. The film’s austere visual style and restrained performances recall the kitchen sink tradition, but its subject matter is anything but secular.

“Throw your burden on Jehovah and he will sustain you,” is the psalm that appears on screen at the beginning of the third act of the film. But what unfolds calls this into question. By situating his drama within the cloistered world of a religious community, Kokotajlo lays bare the spiritual and emotional toll of balancing faith, family, and the burden of belief.

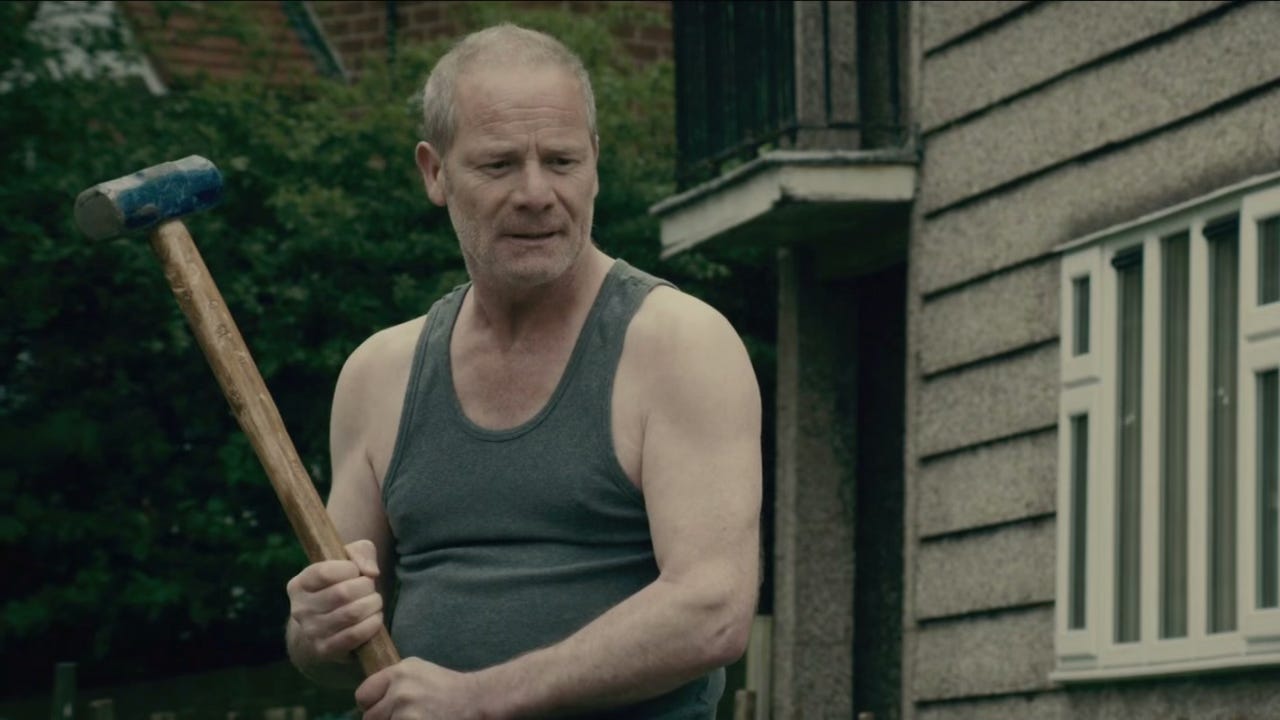

His follow-up Starve Acre (2023), an adaptation of a folk horror novel of the same name by Andrew Michael Hurley, goes one further, merging the raw emotional resonance of Apostasy with a creeping and supernatural dread. In this film, Matt Smith’s Richard - an academic archaeologist struggling to deal with the loss of his child - digs up a hare that he nurses secretly back to life in his upstairs office. The symbolism here is obvious, but it also harks back to a time in Britain’s more religious past when objects were suffused with mystic qualities and spiritual significance - when things meant more than their physical function or dimensions.

Meanwhile across the pond, Robert Eggers, an American director but one with a clear affinity for British folklore, has carved out a niche for himself with films like The Lighthouse (2019). Though his films aren’t strictly British productions, their aesthetic and thematic DNA align closely with this emerging wave. For once, it’s nice to be upstream of America.

The Lighthouse feels indebted to the likes of Derek Jarman’s The Last of England (1987), another film of hypnotic, poetic imagery and a descent into madness. Eggers’ meticulous attention to historical detail and his preoccupation with isolation, faith, and the metaphysical also align him with British contemporaries like Jenkin and Kokotajlo, even as his outsider perspective brings a fresh and typically American intensity to the genre.

Wherever they’re from, I see in these filmmakers a shared willingness to confront the ineffable. They approach their stories with a sense of reverence for what lies beyond human understanding, whether it’s the brutal forces of nature, the hypnotic effects of ritual, the constraints of religious doctrine, or the ghosts of history. Where kitchen sink dramas suffocate us with discomfort to the extent we yearn for release from it, these are films that ask us to accept ambiguity, and to consider that not everything can or should be neatly explained. This marks a significant departure from the social realism of Loach and Leigh, whose narratives, while no less affecting, sought resolution in the tangible struggles of their characters.

So, what does this new wave of spirituality in British cinema tell us, about us?

As I hinted at earlier, I see this wave swelling at a time when secular institutions and norms are being questioned more than ever. The decline of organised religion in Britain has not erased the fundamental human need for meaning and ecstasy. Instead, it has shifted the onus to the arts.

The last few years of last us grappling, collectively and as atomised individuals, with existential levels of uncertainty, stuck in an era defined by political upheaval, environmental crisis, technological alienation, and economic disenfranchisement. When everything is fractured and disorienting, the allure of stories that explore faith, myth, and the metaphysical feel both timely and timeless, and offer us a way out of the stultifying confines of the world as is.

I’m not pretending this genre is an entirely new one, or even that experimental. I’m also not suggesting that I like all of these new films. But, as with any new wave, there is something unique infused within the templates of the past. The shadow of The Wicker Man (1973) looms large over much of this new wave, but the spiritual cinema of today feels less concerned with outright terror and more attuned to introspection. It’s a cinema of questions rather than answers, leaving us at the junction of the sacred and the profane to find our own way back.

This is a fertile new vein of exploration for British cinema. What does it mean to believe? How do we reconcile the seen and the unseen? And in a world that often feels unmoored, where do we find our footing? These directors aren’t concerned with offering easy answers, but perhaps that’s the point. Instead, they linger like sacred shadows on the edges of our consciousness, reminding us that, maybe, this isn’t all there is.

An excellently written piece, though the image captions stole the show. Bravo.